- Home

- Giuliana Rancic

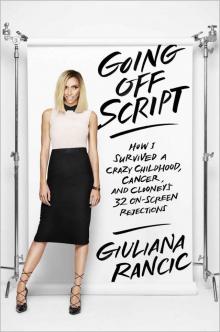

Going Off Script Page 3

Going Off Script Read online

Page 3

I got pretty good at predicting the winner and runners-up, and I fantasized endlessly about someday standing on that stage myself wearing the Miss USA sash and crown. I had some naive notion of making the entire country proud of me (while I blew kisses in the spotlight). I wouldn’t be the dumb immigrant kid anymore. I would win everyone over. I didn’t fantasize about mere approval—what I wanted was public adulation. I had seen what that was like when I was a little girl in Naples and went out with Mama to watch a parade one day. I was nearly swept away by the cheering crowd, but I was too little to see who or what was causing such a commotion. Processions were always winding through the streets in honor of some saint or another, but the size and fervor of this particular crowd signaled something more exciting than another flower-bedecked statue of St. Francis or the Virgin Mary being carried on a platform through town. People were literally weeping with joy, and I jumped up and down, trying to see over their heads.

“Who is it, Mama? Is it the pope?” I asked. As Catholics, we were more dutiful than devout, but I couldn’t think of anyone else who might spark such mob hysteria on the streets of Naples.

“No, it’s Maradona, the greatest football player in the world!” Mama told me. I wasn’t into soccer, but this Maradona’s adoring fan base really impressed me.

“Oh, Mama, isn’t it wonderful that the greatest player in the whole world is from here?” I cried, catching the crowd’s wave of what I now understood to be patriotic pride. Mama looked down at me in puzzlement and shook her head.

“He’s not Italian,” she shouted over the cheers. “He’s from Argentina!”

I wouldn’t have been able to put words to it then, but something clicked and my subconscious took note:

Local approval good.

Universal approval better.

Throughout my childhood, I never once wavered from my twin ambitions of anchorwoman and Miss USA, even as my friends changed their minds a zillion times about what they wanted to be when they grew up. It was like the Christmas doll: This was what I wanted. It was all I wanted. Period, end of story.

I had no clue how I would actually get what I wanted so desperately. I’d have to figure that out later, but I had utter confidence in my own abilities. That was something of a miracle in and of itself, since no one else seemed to have all that much faith in me. As the baby of the family, my dreams were considered “cute” well into adulthood. Everyone treated my aspirations like a joke—Giuliana on TV?—and I was doomed to be seen as precocious instead of passionate. Since they didn’t realize how serious I was, my family couldn’t have known how hurt my feelings were. Besides, the DePandi family already had a star, and her name was Monica. My older sister was smart, beautiful, and hilarious.

Monica and I were mortal enemies, but she was also the object of my grudging admiration and envy. Monica had inherited our father’s discerning eye and exquisite taste. Style was always something I would have to work hard to achieve, but for Monica, it came naturally. So naturally, I borrowed her stylish things—without what might, in a court of law, technically be considered permission or anything remotely resembling it. It would be stupid not to take advantage of the years’ worth of experience Monica had in the fashion department. She was basically the prototype for Suri Cruise. From a very young age, my sister would insist on designer clothes, and my parents would give in to her demands. We were all spoiled, but Monica could pitch a fit like no one else if she was denied. And there was no arguing that she had superior taste. If Dolce & Gabbana had made diapers when she was a baby, she would have worn the samples.

Much as Monica’s shameless materialism made me cringe whenever she wanted a new Versace top or yet another pair of buttery leather boots, my disgust never stopped me from sneaking into her closet when she wasn’t home. Junior high started later than Monica’s high school did, so I would wait for her to leave, then go back upstairs to change into something cool of hers. I was always careful to put things back exactly where I found them later that afternoon, and I even took care not to wear perfume or scented deodorant that would give me away. I’d show up in homeroom, and jaws would drop. Once, I borrowed a pair of cowboy ankle boots, which I proudly wore with slouchy white socks and shorts—not exactly a flattering look for my skinny legs and surfboard feet. My classmates fell over laughing and called me “Rodeo Raheem,” a name that made as much sense then as it does now. “I’ll be laughing in a year when everyone is wearing this!” I shot back. You better believe, every other kid had a pair of those ankle boots a year later. Monica had a knack for forecasting fashion trends. She could also accessorize with the brilliance of a Vogue stylist. I shopped at the Gap and Limited, but Monica worshipped Neiman Marcus and, given the amount of our parents’ money she spent there, the feeling was surely mutual. Even if she wanted to buy a basic white shirt, it had to be the highest quality. She loved the finer things, but to get the finer things, it took money. Cash was her drug of choice. When I was twelve, she even stole the seventy dollars I had saved from leftover lunch money and odd jobs around the neighborhood. When I went to my secret hiding place behind the stuffed animals on my bedroom shelf and the money was gone, I let out a banshee wail that brought everyone running.

“She stole my money!” I shrieked at Mama. “Call the police! I’m calling the police right now so they can arrest her!”

Monica was unfazed. “Oh, stop being so dramatic. I needed it, big deal.”

Mama frantically dug into her purse and produced a sheaf of bills. “Here, Giuliana, it’s okay, look, here’s seventy dollars. Stop crying now.”

“No,” I keened as Monica smugly walked away unpunished yet again. “I want my money!” Mama couldn’t possibly understand my indignation and fury; she let herself get fleeced by Monica on a daily basis and did nothing. Every morning as we got ready for school, Mama would ask us the same question:

“Okay, how much do you need for lunch today?”

“Forty,” Monica would answer, shooting me her death-ray look. Mama would just hand her a couple of twenties without ever voicing dismay at the price of sloppy joes on a high school cafeteria tray. I felt like the silent bystander to the same mugging every morning, and would try to even things out by insisting that I only needed a dollar even as Mama tried to cajole me into taking five. I would often sneak loose change or a few dollars I had saved back into Mama’s purse later. It’s hard to explain why. I realized we weren’t poor, of course; after a year of renting in Virginia, my parents had bought a beautiful colonial house with a pool in Bethesda, a posh Maryland suburb. And contrary to my beloved grandfather’s early proclamations, I was no flaxen-haired angel from heaven: I just wanted, in my childish way, to somehow pay Mama back for all she and Babbo sacrificed to give us whatever we wanted. I believed in karma even before I knew the word for it.

Now that I’m a mother too, I get it that Mama’s need to appease Monica no matter how brazen or bratty she acted probably had a lot to do with having seen her child suffer, and wanting, in any and every way possible, to make it all better somehow. I despised Monica for her attitude back then, but I know today that it would absolutely shatter me if I ever had to see my son endure the pain my sister did as a child.

Monica was in grade school when she was diagnosed with scoliosis, a curvature of the spine that tends to run in families, most typically affecting girls. The causes are usually unknown, and the treatment, in Monica’s case, consisted of spending junior high in a full-torso metal brace, day and night, in hopes her seventy-two-degree curve wouldn’t worsen as she grew. Her seventh- and eighth-grade school pictures show the rod with its metal bar and neck ring sticking up out of her turtleneck sweater. Kids couldn’t help but stare. The physical pain was awful, too. The bowing of the spine causes chronic back pain, but if the C- or S-shaped curve of scoliosis gets bad enough, the rib cage can press against the heart or lungs, causing potentially life-threatening complications. Over the course of a miserable year, the brace did what you would expect such an ugly contr

aption to do to a young girl’s self-esteem, and nothing at all for Monica’s spine. When she was thirteen, we all went to Children’s Hospital in Boston so Dr. John Hall, a renowned orthopedic surgeon out of Harvard, could operate on her. When she woke up, I remember my tough sister moaning and crying in agony. Her body was encased in a cast. From a corner of her hospital room, I watched, wide-eyed and terrified, as Mama and Babbo tried helplessly to comfort her.

“Can you open the window for me?” she begged. “I need you to just open the window.”

“You want some fresh air?” the doctor asked.

“No, I want to jump out,” Monica answered. “I want to die.” I knew, even at eight, that she meant it. Her pain was unbearable to see, much less feel. After a slow and excruciating recovery, an even tougher Monica emerged from the cast. Life, she seemed to be declaring on a daily basis, owed her one. And, by God, she was going to collect.

When it came to pulling a fast one, though, even Monica was no match for our brother, Pasquale.

Pasquale turned fifteen two years after we left Italy, and on his birthday, he informed my parents that in America, all kids got cars when they could drive. And just so they knew in advance, he helpfully added, Pasquale would be wanting a Porsche Turbo convertible. Red, of course. Sure enough, even though the fanciest car in our Virginia neighborhood would have been maybe a Trans Am, and even though our parents drove a modest car, four months shy of his sixteenth birthday, Mama and Babbo tapped into their savings to give Pasquale a Porsche 944 lipstick-red convertible, fully loaded. Pasquale then insisted on having professional photos taken of him posing alongside the Porsche in a black leather jacket and black driving gloves. Off he roared to the tenth grade. It didn’t take long for the school to call Babbo.

“What do you think you’re doing?” the principal demanded. “He can’t drive that car to school!”

“Whatta you mean?” Babbo said.

“It’s not legal,” the principal argued.

“No, Pasquale, he can drive!” Babbo insisted. “He has piece of paper that says he can drive.”

“No,” the principal tried to explain. “What he’s showing you is a learner’s permit. It does not allow him to drive by himself.”

Pasquale wasn’t even grounded for his b.s. job, and he was allowed to keep the car. According to my parents, this was all the principal’s fault, not his. My parents remained more perplexed than perturbed. What was this paper that said Pasquale could drive but couldn’t drive? And what kind of a permit denied a boy permission to drive his own Porsche Turbo? The possibility that Pasquale had done anything wrong was not entertained. “That guy’s an idiot,” Babbo assured Pasquale. “Drive anywhere you want, just not to school.” Pasquale was the prince, the one and only son.

Overindulgent as they were, Mama and Babbo were also extremely overprotective and often illogical when it came to our social lives. It took a long time to convince them to let us go on sleepovers, or even to football games at the school. House parties were forbidden, but nightclubs were allowed, probably because it was considered such a harmless diversion for teens in Italy, where you only had to be thirteen to get in. Every summer, we spent time on Ischia, a beautiful volcanic island in the Bay of Naples. The older kids would all go dancing at the club while the parents socialized late into the night at their own nightclubs or outdoor cafés. “Take Giuliana with you,” my parents always ordered my sister. Monica would dress me in cute clothes and apply full makeup to try to sneak me into the teen club her crowd favored, but it rarely worked, and I usually ended up dancing outside with my friends to the music we could hear booming through the walls.

My parents always refused to leave Ischia before the season there was over, which meant I was always starting school two weeks late in the fall. I would badger them to go back to the United States, but they didn’t see the point: I could make up my schoolwork, but we would never get this time with family back if we relinquished summer now. But I wasn’t the kind of student who could catch up easily once I was behind, and my grades always suffered.

The kind of freedom I enjoyed in Italy didn’t carry over to the States, but I didn’t object: I understood that they were two very different worlds. I remember sitting on a hill with some friends at recess one time in the eighth grade and feeling my blood rise when the American kids started in on how strict my foreign parents were, and how unlucky I was. “My parents are smart, because they know what we’ll do if they let us go to parties and have sleepovers, you idiots,” I said. “They’re the best parents in the world, because they’d do anything for me.” I never touched drugs, or got drunk, or slept around—not because I was afraid of how my parents might punish me, but because I was so scared of disappointing them. None of the three of us kids wanted to ever lose their respect. I still feel that way. But as I entered adolescence, I found a different way to rebel: I became a prankster. In that category, I had way more imagination than common sense, and, for a change, I was utterly fearless. From the age of about twelve on, I occupied a place due north of mischievous and barely south of felonious on the bad-behavior spectrum. I was always hatching crazy, elaborate, sick schemes. Grandma and the Play-Doh Penis Incident was one of the earliest installments of my prankster life.

Whenever my parents brought my maternal grandmother over from Italy for a visit, Nonna Maria would share my pink Laura Ashley bedroom with me, sleeping in the twin bed across from my own. Posters of my favorite celebrities were tacked to the walls. Along with Madonna and whatever boy band was hot at the moment, I had a life-size cutout of another one of my heartthrobs—basketball star Manute Bol. I wasn’t obsessed with basketball, but I was crazy about Manute. At seven feet, seven inches, he was one of the tallest men to ever play in the NBA, and with the polished ebony skin and sinewy build of his native Dinka tribe back in Sudan, one of the most striking. My replica of Manute hung over Nonna’s twin bed. I loved Nonna dearly; she was the one who had taught me to pray as a small child, and every night, we would kneel on my bedroom floor together to thank God for all our blessings, which we would tick off one by one. Tender as it was, that connection we had did not immunize poor Nonna against my wicked sense of humor.

One night when I was twelve, I was hosting a sleepover with friends, and we were all giggling and listening to New Kids on the Block in my room while Nonna snored contentedly in her bed. We decided that we needed to make Manute more noticeable than he already was. I broke out the cans of Play-Doh, and my friends and I went to work. Soon, I was climbing over my sleeping grandmother with our masterpiece in hand, ready to be affixed to Manute. It wasn’t a perfect match: Manute’s complexion was nowhere near the “flesh” color of Play-Doh (seriously, are there actual human beings that sickly shade of melted Dreamsicle?), and the generous appendage we’d sculpted for him kept falling off onto Nonna’s pillow. Eventually, it stuck to him more or less where nature intended it to, and we fell asleep and forgot about it, until my mother walked into my room the next morning.

It was always hard for my friends to gauge just how much trouble we were ever in at my house, or if there was trouble at all, since my whole family routinely conversed in high-decibel Italian with the kinds of theatric gestures Americans usually save for sudden heart attacks, shocking news, or declarations of war, not requests to pass more linguine. The casual swearing also threw most outsiders for a loop, especially when I bothered to translate it for them. My mom could smile like Mrs. Brady, tell me something in Italian, and I’d smile, nod, and say something back, and a friend would nudge me and want to know what she’d said.

“Oh, nothing, she just called me a dumb little bitch,” I’d shrug.

(Shocked silence.)

“Omigod. What did you say?”

Another shrug.

“I told her to go fuck herself.”

I picked up a ton of junior high street—okay, cul-de-sac—cred as the girl who was allowed to curse. In two languages, no less. Being considered cool was something new and exhilarating to m

e, and since all adolescence had given me so far was acne, braces, and a bad perm, I was eager to work with whatever little scraps fate tossed me. “Did you know Julie can say fuck and shit and piss at home and not get in trouble?” a friend boasted one day at the lunch table. I confirmed that I had blanket potty-mouth immunity, and offered to prove it by taking any doubters back to my house for a live demonstration. Mama was in the kitchen and greeted us warmly.

“Mama, I’m allowed to say ‘fuck,’ right?” I asked. Mama said yes, of course, why not, and went about her business.

“Mama, I can say ‘shit,’ too, can’t I?” Another distracted nod. I then turned to my friends like a magician about to perform the grand, saw-the-beautiful-girl-in-half finale. “Now I’m going to say ‘cunt’ in front of my mom,” I announced. My friends gaped as I proceeded to do just that. Mama, having never heard that word before, couldn’t have cared less. My audience was hugely impressed. I smirked triumphantly, and was still reveling in my newfound coolness when I heard a roar and felt myself being picked up by the ankles and thrown to the floor.

“Don’t you ever cuss at her, you fucking little shit, if you ever call Mama that again I will fucking kill you!” My brother, six foot four and seven years older, then proceeded to swing me head first against the wall while I screamed at the top of my lungs. My friends looked on; this show just kept getting better and better. “Pasquale, why-a you killing your sister?” Mama shouted over the commotion, stopping short of actually forbidding Pasquale to murder me.

Pasquale’s God status made him the perfect fodder for what would turn out to be by far the worst prank I ever pulled. I was twelve or thirteen, and I was up in my room talking with my friend Matt Donnelly when I got the brilliant idea that we should prank my mother. “Okay,” I instructed Matt, “let’s conferencecall my mom, and you pretend to be a police officer.” I went over his lines with him, and we dialed Mama. I could hear her pick up downstairs.

Going Off Script

Going Off Script